In our Open Voices blog we share insight from leaders in our communities who are advancing what it means to have sacred, open green spaces in our cities. This month we examine the need for equal access to healthy urban spaces.

A decade ago New Orleans faced dramatic floods and destruction following Hurricane Katrina. This landmark of a city, famed for its culture and vibrancy, faced institutional and structural obstacles across all scales. Civic participation bloomed in response to the need for everyone to pull together.

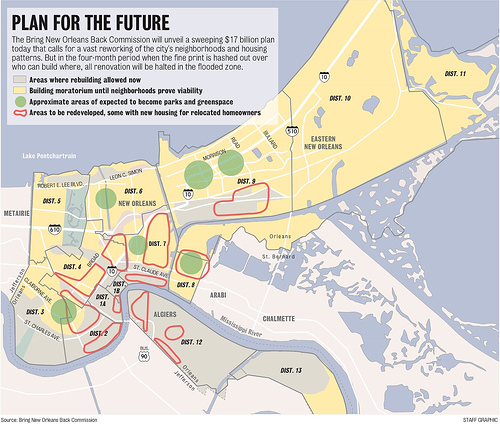

Researchers and news outlets have poured over every development and rebuilding decision since 2005. As we approach the 10 year mark on August 29th, a tone of cautious celebration is emerging. The Atlantic asks if New Orleans will be America’s ‘Next Great Innovation Hub’ and Forbes is nothing but positive over the prospects of new tech startups, hotels, and local innovation. But just yesterday the Public Policy Research Lab at Louisiana State University revealed what other studies have also speculated. A racial divide between the quality of schools, life and the local economy persists in ways more similar to pre-2005 than we would hope. This is in part due to the grim fact that African Americans were far more likely to have lived in a flooded part of the city and these places have taken much longer to recover. For those who returned to their neighborhood, or never left, their perception of recovery is not as bright as Forbes.

A research article released last summer reviewed one interesting angle of recovery. Yuki Kato and colleagues1 describe how urban political gardening took hold in the neighborhoods hardest hit by the flooding. Urban political gardening is not a strict, organized action per se but ways in which various gardening projects exhibit different levels and scopes of political engagement. As we close this month’s blog on Environment Equality, we examine how urban gardens represent, challenge, and are shaped by local issues. In the case of New Orleans, urban gardens can provide sustenance to the minds and bodies of those most in need, but reveal much in the process.

Community gardens in the U.S. have been established in times of major crises and social disruption 2. War, natural disaster, and personal trauma have inspired many Americans to search for hope in the garden. Keith Tidball, a Nature Sacred research partner, has contributed extensive research on ‘Greening in the Red Zone’. An ongoing project in a post-Hurricane Sandy community garden space provides an interesting comparison to post- Katrina New Orleans.

Community garden spaces can be critical in reiterating community identity. Each provides a space for neighbors to see each other face to face and contribute in ways free from financial constraints. In New Orleans, the scope and durability of community gardens is diverse. Between 2009 and 2012, Yuki Kato’s team interviewed and visited several community garden spaces. Rather than witnessing how a garden space transformed a community, their research revealed how such green spaces suddenly reveal the social conditions of a neighborhood. In every instance there was an apparent lack of healthy food options, grocery stores, public space and cross-cultural communication.

For example, Hollygrove Market and Farm was established only a few months before Hurricane Katrina. Hollygrove is a predominately African American working-class community that experienced flooding up to six feet. The Market and Farm persisted and now maintains an on-site community garden and growing site providing produce for the daily food market. Despite the success of the market, HMF has struggled with engaging local residents in its ongoing needs. Local residents do not populate the market as much as more affluent neighbors but residents do constitute the majority of garden volunteers. Volunteers thought other neighbors’ lack of interest in gardening could be attributed to tastes, time, access or having a garden in their backyard. The volunteers expressed a range of motivations from personal healing to a solution to a failing food system:

“And I said, my! it was just amazing. Like I said, I never did something of that nature, and its just awesome”.

“So this is a way that we can combat all of that. Maybe that’s how you want to play. Guess what, I don’t need you. I can grow what I want”.

For New Orleans, many green spaces are new and growing. Unlike New York City, where post-Sandy community gardens have rebounded and revealed strong community ties and resources, New Orleans green spaces were not as dense and tangled in the social fabric 3. New Orleans may be a clear example of how green spaces represent and reflect the hard truth of community needs. Green spaces (whether community gardens, parks, or tree lined streets) provide places of healing and respite but also create a visual reminder of the ongoing needs and desires of a community.