Each month in our Open Voices blog we share insight from leaders and ideas advancing what it means to have sacred, open green spaces in our cities. This week we examine the aesthetic and poetic elements of civic sacred.

“The city has been likened to a poem, a sculpture, a machine. But the city is more than a text, and more than an artistic or technological artifact. It is a place where natural forces pulse and millions of people live–thinking, feeling, dreaming, doing. An aesthetic of urban design must therefore be rooted in the normal processes of nature and of living. It should link function, feeling, and meaning and should engage the senses and the mind.”

In The Poetics of City and Nature, a writer calls for a new aesthetic theory of landscape and urban design. Anne Whiston Spirn wrote in 1988 that the idea of dialogue in creating a city is central. How we interact and move about in a city is the result of complex, overlapping and interweaving narratives.

How have we created a cooperative, evocative, meaningful cityscape since? In 1988, cities had community gardens, cooperative design making, and green spaces serving ecosystem and recreation needs. We had less of these, less language and data to talk about the benefits, and certainly less spaces supporting moments of quiet contemplation. Today, one strong example of how art, dialogue and community weaves into open, sacred spaces is through the practice of place-making.

Place-making is community-based participation resulting in quality, healthful public spaces. It is a process of identifying local community assets, needs, inspiration, and potential, and it results in the creation of quality public spaces.

This week, let us celebrate the recent history of poetic narratives of city, nature and art.

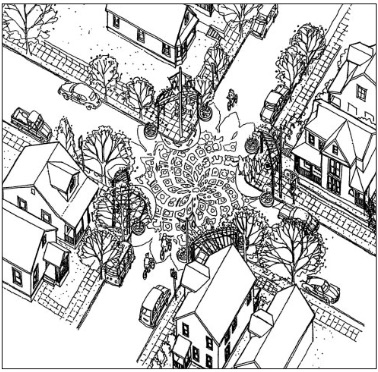

::In the late 1990s, the Sunnyside neighborhood in Portland, Oregon invigorated neighborhood stewardship by organizing and creating a public gathering place. The neighborhood was experiencing an increase in undesirable elements such as crime, vandalism, and traffic violations (speeding through the residential streets). The neighborhood decided to paint a gigantic sunflower in the middle of an intersection and installed serval interactive art features. Since the 2000s, the Sunnyside neighborhood has inspired others to reclaim their residential areas with art and meaningful place markers.

::Dufferin Grove Park in Toronto, Canada (established in the mid 1990s) is bumbling with activity today. Dufferin offers quiet groves for contemplative moments, traditional playgrounds, community run campfires and a farmer’s market. Perhaps what it is most known for is the nature-feature playground with a giant sand pit, running water, wading pool, garden shovels and real logs. All of these natural features provide opportunities for nature engagement. Children can build labyrinths of water streams and bridges, even mini-ponds. Dufferin will not win any design awards, but it’s 2001 international award as a “Great Community Place” comes from its intentional nature encounters, art engagement, and community-responsive resources.

::A plot of land that was once used as the final resting place for 2,000 U.S. marines and navy crew is being transformed in 2015 into a lush waterfront. In addition to design and construction, Brooklyn Greenway Initiative researchers partnering with The Green School of East Williamsburg and Brooklyn Community Housing and Services (BCHS) are studying the effects of nature on stressed communities.

::A plot of land that was once used as the final resting place for 2,000 U.S. marines and navy crew is being transformed in 2015 into a lush waterfront. In addition to design and construction, Brooklyn Greenway Initiative researchers partnering with The Green School of East Williamsburg and Brooklyn Community Housing and Services (BCHS) are studying the effects of nature on stressed communities.

Using the open space and eco-meadow as a laboratory, ninth-grade students at the new Green School are learning about soil science, hydrology and biology. The students also aided the project landscape designers in imagining and designing future use of the space.

“Everyone has the right to live in a great place. More importantly, everyone has the right to contribute to making the place where they already live great.” -Fred Kent, President, Project for Public Spaces