This month as we examine the cognitive benefits from being in nature we talked with Matt Stevenson of the University of Copenhagen. Stevenson is a PhD fellow in the Forest and Landscape College and one of many emerging, dynamic projects developing out of the Centre for Outdoor Life and Nature. Stevenson represents many new scholars around the globe contributing in new ways to health and nature research.

Nature Sacred: How do you like living in Copenhagen? What kinds of parks and outdoor activities are there?

Matt Stevenson: It is nice. It is different than what I’m used to. I come from a small town in New Zealand compared to here. It is about 40,000 people. There are over a million people in Copenhagen. The big thing in Copenhagen is riding bikes. There are a few parks but access is quickened by bike riding. Further north of Copenhangen is a forest. A European beech forest (coastal Forest) environment, which is different to what I’m used to. The department I am in is called ‘Skovskolen,’ which translates to The Forest School, a resource management department similar to those in the U.S. But the whole department is actually based inside of a forest. It is about an hour and a half north from where I usually am in Copenhagen. My favourite spot in Copenhagen is a big green park-like cemetery near my apartment. My ‘home base’ where I like to read, relax, and watch squirrels.

What research questions were you asking as a Masters student in New Zealand?

I was looking at neural mechanisms and cognitive development in children with ADHD diagnoses, but not looking at the role of the outdoors. While I was a post-graduate student I was reading more and more about environmental psychology but there was no one doing it at my old university. I was traveling and reading a lot after my degree completion and read Last Child in the Woods. That’s when I said, ‘This is it’.

Your project builds off of research from Nature Sacred partners Frances (Ming) Kuo and Marc Berman and has a quantitative component many are excited to see.1,2 Tell us about your research project.

The research I am doing, in the general sense, is looking at how the natural environment influences the brain. But I am also considering mental health and education practices. My dissertation consists of several projects.

The first project is examining executive function in healthy, non-diagnosed children (7-12 years). I am examining how different types of attention is affected (or unaffected) by natural environments. Pre-existing, standardized cognitive tests allow us to consider which circuits within the brain may be sensitive to experiences in nature. These tests often have a substantial history within the fields of psychology and neuroscience. For example, imaging techniques can show us what areas of the brain are used while performing the task.

These tests can examine skills that are important for success at school, such as executive or directed attention, the ability to focus while suppressing distraction. For example, a computer-based test called the Attention Network Task measures three types of attention, including executive attention, in a game-like setting with a fish swimming to the left or the right. Participants push a button according to directions but are sometimes intentionally distracted on screen. When the distracting fish are swimming in the opposite direction to the target fish the participant must overcome this distraction in order to respond correctly. This skill is associated with a distinct circuit within the brain.

Children will complete these tasks, as well as other measures meant to capture mood and induce mental fatigue. After these tasks, children will walk through a forest setting for a set time. This forest walk is theorized to be restorative, a brain break. After the walk the children will complete the attention tasks again. Their performance before and after will be compared and analyzed.

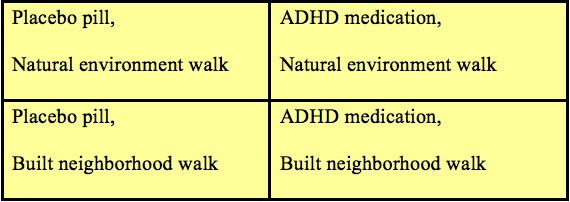

The second project will occur in New Zealand in partnership with the University of Otago. This seeks to compare the effect of time spent in nature with pharmacological treatments for children diagnosed with ADHD. It is a double-blind, randomized controlled study. (This research design is considered the gold standard and will provide evidence comparable to Western medical research). This project will test at the beginning of the child’s day, using the attention tasks. The participants will take their prescribed ADHD medication or a placebo pill at their regular morning time and then walk in a natural environment or in a built, neighborhood environment. The design will have four conditions (groups).

This research design helps us ask “Will there be short-term effects from spending time in nature similar to pharmacological benefits? Does a walk in a natural environment enhance the effect of medication? Plus is there additional benefits from spending time outside beyond cognitive performance?” (Research from other nature and health studies hint at benefits to children like creativity, general well-being, positive emotions.)

In the last study, back in Denmark, I will examine spending time in nature as part of the mainstream education system. I will be creating a schedule where the children spend their free time/recess and lunch in natural environments. Another group will spend their lunch or recess in their normal indoor school space. Then they’ll switch groups. I am measuring executive functions (using the attention tasks described above) but how it relates to functional outcomes like social behaviors and learning skills. Improvements in cognitive skills have so far been measured in the short-term because that is how they are designed. But we are interested in the practical, longer benefits over a 6-week period.

The Nature Sacred research initiative is supporting several projects examining topics similar to yours. One major question across these projects is whether there is a healing role of nature in addition to encouraging physical activity. For example, we know that green exercise (for example, running in a forested trail) benefits people cognitively and emotionally differently than running around an indoor track. And we know there are cognitive, emotional and stress relief benefits from light activities like gardening, viewing trees in the wind, listening to water sounds, or simply viewing images of nature on a screen. For children, what benefits might exist from playing in a natural space in addition to ‘gross motor play’?

In this school study, the children will visit a nearby nature place during lunch or recess. It might be a wooded area or a park. It will not be a built structure. We think being in a natural environment might stimulate you to be more active or more creative. The difference might come from the novelty effect of being in a different space. It might promote different physical activity. Built playgrounds are designed for physical activity, but natural environments are not necessarily explicitly designed for this. There are no boundaries, no directed play. Using the space requires creativity. School grounds are designed for a purpose, are designed to benefit children. But it is not always the case that a child uses it as it is designed. A natural environment is just there (even if planted and not original). It really opens up a huge amount of different elements and possibilities.

Your department, The Centre for Outdoor Life and Nature, is an exciting nexus of emerging and renowned scholars investigating the healing effects of nature. What kind of research projects are underway?

TEACHOUT is an outdoor education research project looking at the benefits of teaching outside the classroom. Udeskole, similar to forest schools in the UK, refers to curriculum-based teaching outside of school in nature or cultural settings. One day a week children may be in a museum but a lot of what they do is outside. This kind of teaching practice has been going on in Denmark for quite a while. A school reform last year from the government encourages this type of teaching and wants to support research into the benefits of this format. TEACHOUT is looking at social skills, physical activity, learning and development as outcomes from the udeskole model. This project is also asking how teachers are responding to and benefiting from this format, and their opinions. When I first started my research I reached out to this group and I am now working parallel with them.

Another research group in my department, although I am not working with them, have designed eight different restorative natural environments in nearby nature settings. This research group are all landscape designers and they based their designs on restoration design principles. Nature gardens and healing gardens, for example. Across these different spaces they are researching mental health benefits. Another project is examining the benefits of therapy gardens for people experiencing severe stress.

What is important for people to know about your research? And nature benefit research in general?

As I read the existing literature about nature and the brain, one thing that stands out to me is the effect nature seems to have on self-regulation and the value of the emotional benefits from being outside. Controlling your motivation and behavior and how being outside benefits that. There is a strong benefit. I think the benefit of self-regulation bridges the gaps between emotions and cognitive function. Being able to control your emotions so you can perform well cognitively is significant. The interrelatedness of cognition and emotion is a complex puzzle within the broader psychology research field.

Using the Attention Network Task, Berman et al. (2008) showed natural environments can improve this skill in university students. I want to see if this is also true for children.

I love the possibility that nature can benefit everyone. An interesting finding from a study in Holland showed that you can benefit from time spent in nature even if you don’t like it. This finding suggests that nature is potentially beneficial for everyone despite your attitude. This idea might have implications for nature being considered as a supplementary treatment in mental health practice. Medication typically given for ADHD, Ritalin, has a stigma and a lot of side effects, and not everyone diagnosed with ADHD responds to Ritalin. But, theoretically if you have a human brain being outside should be beneficial – everyone is a ‘responder.’

I am also excited about new nature benefit research that includes brain imaging techniques, and the research I read about on your website for veterans and people with severe stress or anxiety.

NS: Thank you for your sharing your work with us. We wish you well in your progress.

—–

Transcript has been edited and paraphrased for formatting.

Citations: