New research from a Nature Sacred partner, Frances Kuo at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, hints at a central pathway linking human health and time spent in nature.

Taking a walk in the park, going for a hike, or watching a tree sway in the wind feels intuitively relaxing. Health and nature research takes this a step further by asking how much, how often, and under what conditions humans benefit from spending time outside. Understanding what is happening outside of our awareness is where the scientific process steps in. In an era where more and more people are moving into cities, it is certainly worth our time to know how to build healthy urban spaces. And it is certainly worthwhile to assess the causes and correlations of nature-based health outcomes.

What conditions in our urban green spaces promote health? Exercising outside, breathing cleaner air, robust biodiversity? Does resting in a nearby park promote better sleep, increased social ties, or stronger immune systems? Kuo’s research review suggests nature’s ability to enhance immune functioning may be the major reason behind a host of health benefits.

One of the chief functions of the immune system is to ward off infectious disease, protecting the body from bacterial, parasitic, fungal, and viral infections. The immune system also assists in wound healing and tumor cell destruction, is suspected to play a role in ADHD and migraines, and governs inflammation, implicated in allergies, anxiety disorder, eczema, and a diversity of other health care needs.

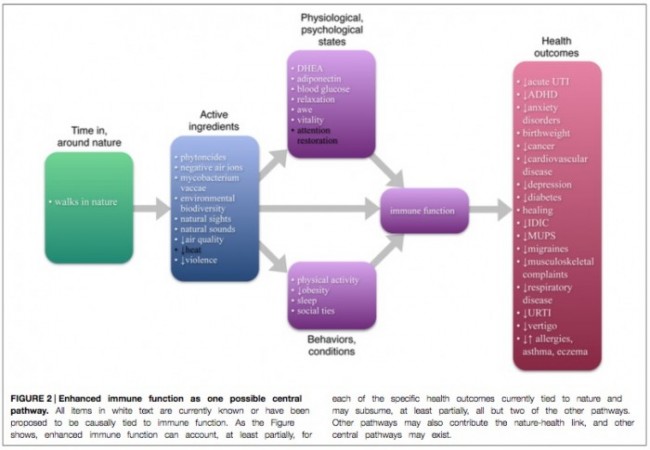

In the diagram below, all items in white text are currently known or have been proposed to be causally tied to immune function. Enhanced immune function can account, at least partially, for each of the specific health outcomes (pink box) currently tied to nature. Enhanced immune function can account for, at least partially, all but two of the other pathways (purple boxes). Kuo notes that other pathways may also contribute to the nature-health link, and other central pathways may exist. Further research can reveal this.

The range of specific health outcomes tied to nature is staggering. In general, the more contact with nature, the better the health outcome, even after controlling for socioeconomic status and other factors. Improvement during and after time spent in and around green spaces is linked with depression and anxiety, diabetes, ADHD, various infectious diseases, cancer, healing from surgery, obesity, birth outcomes, cardiovascular disease, migraines, respiratory disease, and others.

These documented health improvements may be due to a whole host of conditions and states but whether all are equally the cause is yet to be understood. They might be due to environmental conditions such as cleaner air, less noise, soil microorganisms, or cooler temperatures from tree shade. Or, plausible pathways between contact with nature and health may come from changes in physiological and psychological states: improved immune system functioning, stress reduction, experiences of awe, and improvements in attention.

In a review of existing literature, Kuo proposes a healing pathway may plausibly account for the bulk of the tie between nature and health if it has a large effect, exists in many different places and situations, can account for specific health outcomes, and can subsume other ‘smaller’ pathways. Based on her review, Kuo suggests immune functioning is the central pathway linking time spent in nature and health improvement because it fulfills all these conditions of a central pathway to health.