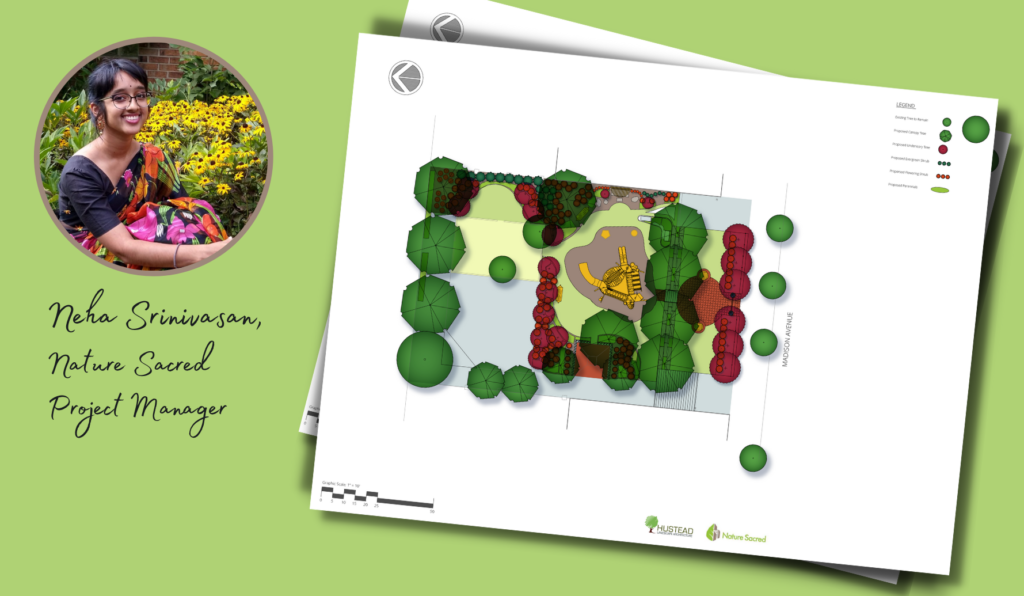

Our Design Advisors, a team of landscape architects and designers, have been an integral part of the Nature Sacred approach since the conception of our first Sacred Place. Centering design and elevating its importance is a unique position for an organization to take: one thing we’ve observed through the years is that most people’s idea of what a landscape architect does is limited compared to reality. So we thought, why not address that disparity? And Neha Srinivasan, as our Sacred Place Project Manager and a landscape designer herself, was the perfect person to navigate us through her field. Here’s her take on landscape architecture and the many ways in which it contributes to healthier, more joyful built environments.

When I’m asked what I do, and people hear the term “landscape architecture,” their first response often is, “That’s amazing! What kind of buildings do you design?” My friends seem to think my job involves talking to plants (that much is true), but beyond that, the field appears to be an elusive one for folks to define.

I recently went to a small gathering of landscape architects, and someone with far more experience than me said that it’s nice to be back with people who know what we do — that we’re the only ones that really get it. While this is going to be true for any profession, it’s particularly true for us. But for a field whose work everyone inevitably interacts with every day, it’s astonishing that there remains such a mystique around it.

So what does it mean to be a landscape architect?

The best way I’ve found to explain it is this. If you look outside, almost anything you see that’s not a large building, we’re probably equipped to design. Topography, plantings, water features, yes — but also streets, sidewalks, lighting, walls, drainage, outdoor furnishings, play structures, and art features. However, those are surface-level things; the principles of the field go far deeper.

Fundamentally, landscape architects are responsible for melding structure, function, and aesthetics to create imaginative places that provide enduring value to the planet and people.

Let’s deconstruct that statement. In the biology world, the structure-function relationship is a pretty big deal. It means that the structure of an object or organism determines the function it serves. Similarly, landscapes need to be physically laid out in specific ways to be able to serve their intended purpose, whether that is to decrease carbon emissions, increase pedestrian safety, or foster community cohesion. To provide value to the planet, you have to understand how ecosystems work, the current and future effects of climate change, and how to make sure people want to keep your sustainable design around. To provide value to people, landscapes have to be designed with their context in mind. That often means having a solid grasp of environmental psychology (what humans find safe, exciting, and aesthetically attractive), doing research on the location, and designing in a way that welcomes engagement from a diverse pool of local users.

As we collaborate with communities and listen to the dreams they have for their spaces, we use our own artistry to take this deep knowledge to find innovative ways to interpret their ideas both conceptually and physically in the space. And all of this has to be integrated seamlessly and translated properly into a spatial vision — think those design elements I mentioned at the beginning — that looks good not just the day after it goes in the ground, but one, ten, and fifty years after.

That’s a lot of considerations, especially for a job that often goes unnoticed. (Not many of us are in the habit of notifying the stormwater department when the storm drains are working perfectly, but we’ll all complain if the drains flood.) Landscape architects are, unfortunately, accustomed to our budgets being the first to be cut on a multidisciplinary project. Nature Sacred is unique in having recognized since its inception that landscapes are an essential service — something many are only just starting to realize. There are a plethora of reasons this ethos isn’t yet the norm — we’re accustomed to looking at landscape as an amenity; it’s easy to assume picking out plants is not that difficult a job; the long-term impact provided by landscapes is harder to fathom; the cultural value of nature has been eroded — and we could unpack this all day. But more importantly, what do we lose when this is the way we see nature and the people who steward it?

First of all, for too long, humans have viewed nature, land use, health, equity, economics, and more as mutually exclusive. More and more, we are discovering that these are all actually highly interlocked issues. Our historical patterns of land use, our attitudes towards our natural resources, the way we prioritize who has access to resources, have created countless problems, but the flip side is that they can (and should) all be addressed together, systemically. And landscape architects are a natural fit for helping solve these problems. We are trained to be a nexus between fields, to connect ecologists, planners, architects, engineers, and communities. To be able to navigate and balance all these fields, ensuring that their various goals work in synchrony, requires a great deal of technical competence: the skills to tease out a community’s desires, the large-scale vision to assemble a cohesive concept, and the precision to understand and build on technical specifications to a minute level.

The sheer scope and variety of what a landscape architect’s work can entail means we have far-reaching, highly interdisciplinary analytical processes — and we’ll give you a solution that not only works, but lasts.

Second, though humans spend a large amount of time indoors, it’s our outdoor spaces that form the matrix between buildings — and as such, our outdoor spaces are really the ones that knit together the fabric of a place. Baltimore wouldn’t feel like Baltimore without its rowhomes, just like New York wouldn’t be the same without its gridded streets. If we all thought about our built environments not as individual buildings with gaps in between, but as portions of one connected landscape, we could add so much more unity and nuance to the way we craft them. If a single, small, well-designed pocket park — a Sacred Place — can promote well-being, community cohesion, sustainability, and resilience, all at once, imagine what that approach could do if applied across a neighborhood, a city, a watershed. We are shortchanging ourselves if we don’t utilize the outdoor space we have. People should have options: not just the option to be inside or outside, but the option to be outside in a green space they love.

Third, when we love something, we feel a sense of stewardship over it; we want to learn about it.

Many cultures have deep-rooted connections to nature, but for many people, and often particularly those of us who grew up in cities, those connections are shrouded. Rediscovering nature by exploring a landscape we feel connected to teaches us to respect the world around us and those we share it with — and it can inspire us to learn how to care for it better.

Why is this so crucial? Why should a community have green spaces that acknowledge its own cultural truth and lived experiences? Well, representation matters. Everyone has the right to feel that they belong in a space, and that’s as true for green space as it is for our schools, hospitals, and cultural institutions. And by working to spotlight, through the medium of physical space, the unique stories of ecosystems and communities that have been and continue to be marginalized, we can reflect their light back onto them.

So what do we lose when we omit landscape architecture from the conversation? We lose cohesion, intentionality, and the ability to learn from our surroundings. Whether we notice it or not, landscape and its design are embedded into our everyday lives, just as much as our bedrooms and kitchens. For those rooms, we spend weeks deliberating between sage green and mint green paint swatches; why would we not bring that same intensity of focus to our outdoor spaces, which can achieve so much more if we only let them? Landscape architecture has the unique ability to reframe our living environments for the better, to bring the planet not just a more vibrant future, but a more joyful and equitable present.

— Neha Srinivasan, Nature Sacred Project Manager