About this Sacred Place

Even on a cold and windy November morning, there’s something peaceful about the path that meanders past the community garden at Arlington County’s Barton Park. The smell of pine needles is strong in the air. Blowing leaves are scattered across the smooth river stones that nestle beneath the boulders that border the walk.

The labyrinth there was once at home outside of Whitman-Walker Clinic at Lee Highway and George Mason Drive. When the clinic closed in 2009, the labyrinth’s stones were pried from the earth — the pieces of its seven-circuit path of contemplation painstakingly numbered and stored in a county warehouse. It sat there for four years until 2013 when three acres of land became available at 10th Street North and North Barton Street.

The story of its relocation began several years before this, when the county received the use of the land from a developer and began talking to neighbors about their plans for the space. Rocky Run Park, of which Barton is a part, was rebuilt for active recreational activities with playgrounds and ball courts. Neighbors sought a quieter, more contemplative space on the south end, near 10th Street North — someone even mentioned the possibility of a labyrinth.

Kathy von Bredow, a county landscape architect, walked through the property and saw potential in its large trees, which created a sense of isolation despite the nearby busy streets. She spotted a huge white oak that struck her as a “mother tree” that could give the site direction and focus. She knew the clinic’s labyrinth was in storage. It seemed to her that this was the place for it.

When Arlington County employees first took the labyrinth out of storage, they were faced with a massive puzzle. Although the stones had been carefully numbered and mapped, the numbers had been written in chalk, and some had worn off. Fortunately, photos of the original path had been taken and some of the same people who created the original labyrinth pitched in to work on the new one.

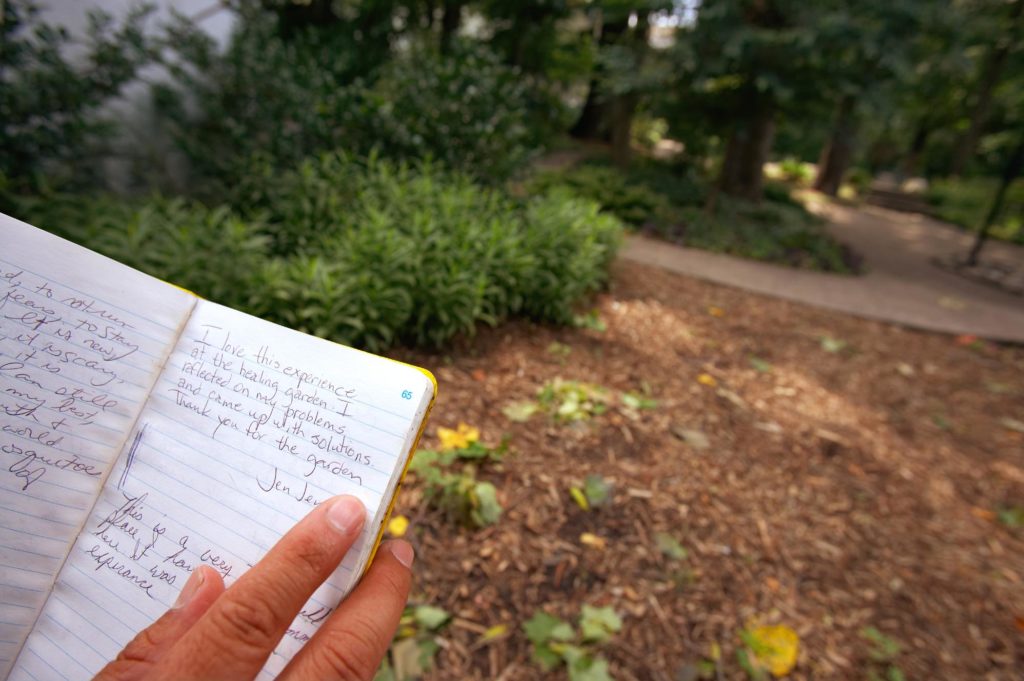

The rebuilt labyrinth may have added resonance for the gay community. Even as late as the 1990s, when the District’s Whitman-Walker Clinic sought a site in Northern Virginia to serve HIV-positive patients or who had AIDS, Arlington was the only jurisdiction that welcomed them, said Fisette, who is gay. The clinic rented its space with a back lot tangled with weeds and overgrowth. Volunteers pitched in to clear it and design a private healing garden. Because clinic funds could not be spent on nonmedical initiatives, donated money and talent were necessary.

Today, the labyrinth at Barton sits at the quieter end of Rocky Run Park, a nice complement to the playgrounds, playing fields and recreational areas at the other end. This side sees community members daily — walking their dogs, tending to their plot in the community garden that sits adjacent to the Sacred Place, or just on a stroll to enjoy the outdoors. Once a bare and dormant patch of dirt and grass, Whitman-Walker’s labyrinth relocation breathes new life into the space.