Sacred Places are a veritable garden of different shapes and sizes. Some, humble patches of green — pocket parks; while others can be described as wild and rambling. A common thread among all, though, is their role in drawing communities together. And that is something, most would agree, we sorely need today.

While nature itself is magnetic, what we’ve learned from our decades of work is that for green spaces to thrive, nature often needs a helping hand. Within Sacred Places, Firesouls are that helping hand. And meeting with them is pretty much the best part of my job — understanding the ways they creatively convene people from all walks of life in nature.

Join me on a visit to a very unique Sacred Place that serves a diverse, bustling intersection of many communities in Baltimore. I’ll share a bit of my travel log: ideas, inspirations and images grabbed along the way.

Meeting up with Firesoul Jennifer Robinson

Today, I’m happy to report to you from Patterson Park and to share what Firesoul, Jennifer Robinson, in collaboration with Friends of Patterson Park and Baltimore City Recreation and Parks, is doing to provide stewardship, events and outreach to the community. Think organized sports, festivals, small concerts and summer camps. They’ve been so successful that the park is known by the locals as The Best Backyard in Baltimore.

Patterson Park comprises 133 acres in southeast Baltimore and is the oldest park in all of Baltimore City. Here you’ll find open fields of grass, large trees, paved walkways, historic battle sites, a lake, playgrounds, athletic fields and a swimming pool.

A little slice of history

The land that now holds Patterson Park as well as the greater Baltimore area has a human history that stretches back 12,000 years. Indigenous people, dozens of tribes through the centuries, traveled through and made this place home. Once Columbus arrived, native populations were largely driven West. Today, organizations like the Baltimore American Indian Center are working to keep their stories alive.

In more recent history (1814), the elevated ground — Hampstead Hill — close to the Port of Baltimore, was the meeting point for Baltimoreans looking to thwart a British invasion. It worked.

A brief 39 years later the park was made a public space by the city — with 20,000 people gathered to celebrate.

The People of Patterson

Butcher’s Hill, Upper Fells Point, Little Italy, Highlandtown, Linwood and Canton — these are a few of the neighborhoods that consider Patterson Park their own. This space also attracts an amazingly diverse mix of Southeast and East Baltimoreans, with a cross-section of adults and kids spread out among its baseball, football, and soccer fields; on its basketball and tennis courts; and, in the warmer months, at the pool or on the park’s nearby hillside, eating handmade ice cream from Eastern Avenue’s BMore Licks.

How to: Engage the community

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Patterson Park has been a haven for surrounding residents seeking nature as well as a safe connection with others. Jennifer and her team have supported this through extensive virtual programming including Zumba and children’s “Jungle Gym” classes; mindfulness sessions and walking tours; photo contests and a step counting competition for kids. Bi-lingual yoga supported through a Nature Sacred enrichment grant has also been on offer. An annual Pagoda lighting features silhouettes of historic park pastimes and snowflakes created by community members.

Most recently, Friends of Patterson Park announced the East Baltimore Winter Olympics: a family-friendly scavenger hunt-like event that will run from Thursday, March 4 through Sunday, March 21.

A look ahead

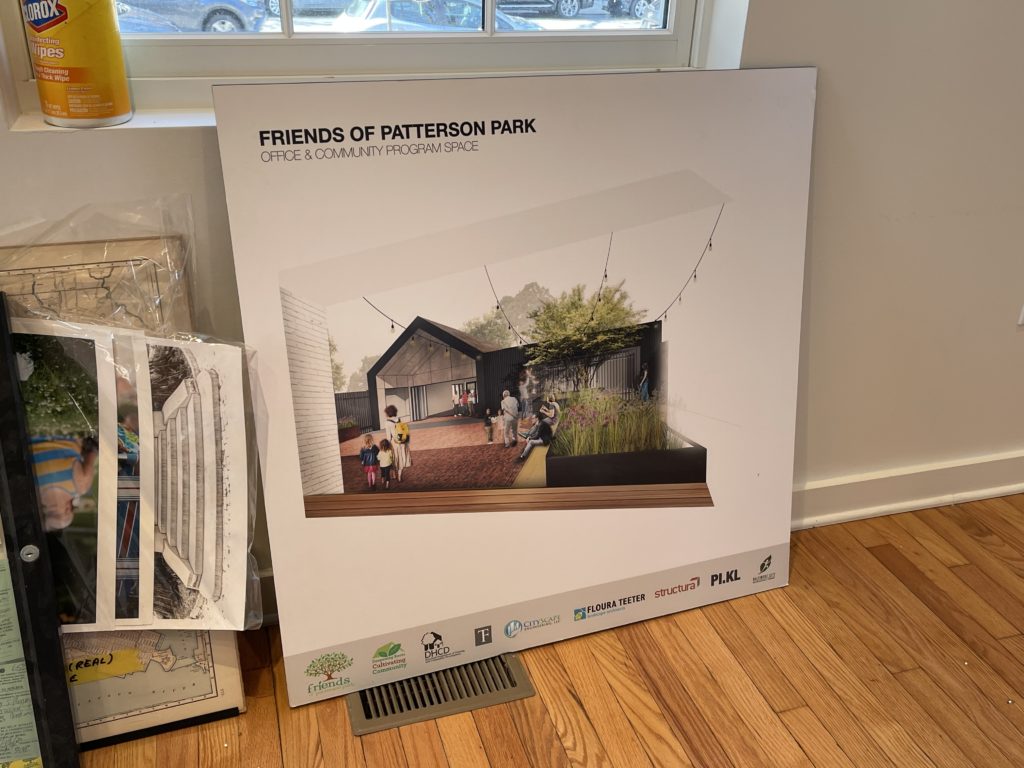

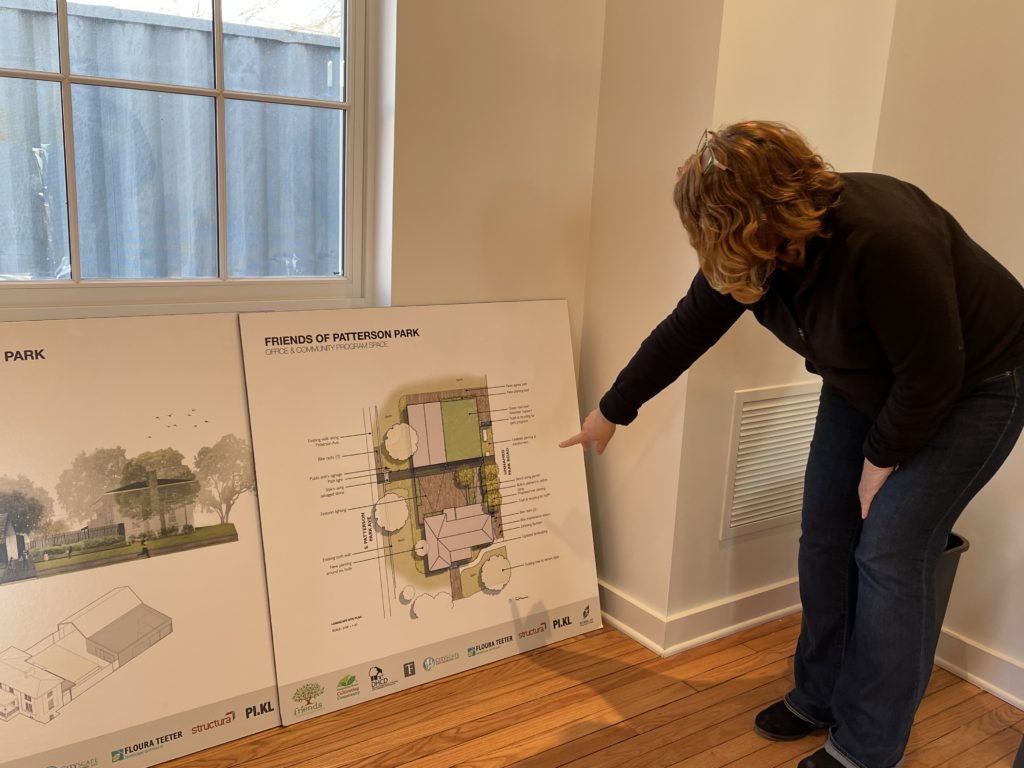

On the day I visited, together with Nature Sacred Design Advisor Jack Sullivan, Jennifer led us on a walk through the park, giving us a sneak peek of their newly renovated offices — the former Patterson Park superintendent’s house located in the northwest corner of the park, a historic 1868 building that has had no major improvements since the 1970s. The construction of an adjacent Community Space will support flexible indoor programming and a Volunteer Support Center (featuring a green roof) will make tools safely available to volunteers. A courtyard and garden will serve as additional programming areas. This site was designed by Floura Teeter, whose principal, Joan Floura, is another Nature Sacred Design Advisor.

Together, we were also eyeing sites to install two additional Nature Sacred benches. Jack made two suggestions: the first, an area close to the Dr. Levi Watkins Jr Fountain — pictured below — which was designed by George A. Frederick (who also designed and built Baltimore’s City Hall). This was the very first architectural element erected in Patterson Park in 1865. It was also one of the first restoration projects undertaken after years of neglect and vandalism left it dilapidated and inoperative, through a grant from us at Nature Sacred! We love how this historic fountain serves as a long-time gathering space for the community to socialize, as well as a spot to quietly enjoy the soothing sounds of the fountain’s cascading water.

The second location is a satellite site of the Nature Sacred UMBC Joseph Beuys Sculpture Park. In 2002, as part of the Tree Partnership, over 200 trees were planted among Patterson Park, Carroll Park and Wyman Dell Park, all within Baltimore City, in connection with the 30 trees and stones that were placed at UMBC’s sacred place. Through the Nature Sacred Network, Jennifer is working with Sandra Abbott, Firesoul at UMBC, to think of innovative ways to better communicate the importance of this site through signage and other promotions. Our Network at work!